Xanthos is more than an ancient city—it’s a crossroads where Lycian resilience, Persian power, and Hellenic grace fused into a legacy that still challenges how we tell the story of the ancient world.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Xanthos

On a bluff above today’s Eşen River, Xanthos rose as the proud capital of Lycia—one of Anatolia’s most distinctive civilizations. Twice in antiquity (first against the Persians in the 6th century BCE, then against Brutus in 42 BCE), the Xanthians chose to burn their city rather than surrender.

Xanthos, is an ancient Lycian city and UNESCO World Heritage Site with its rich blend of Lycian, Greek, and Persian influences. Designated in 1988 alongside the nearby Letoon sanctuary, it features impressive ruins such as tombs, temples, and a theater that reflect the region’s unique cultural and historical significance.

That stubborn courage isn’t just legend; it frames how we should read the stones: this is a place where a deeply Anatolian identity held firm while interacting with Persia, the Hellenic world, and Rome.

Friend Glaucus, why are we named lords in Lycia,

poured the first wine, carved the choicest meat?

Not for soft benches or garlands alone—

but that we stand where spears knit night from noon,

our shields a wall, our hearts a burning oath.

If death could be refused like a poor gift,

we’d let the lesser strive and keep our lives.

But since no man outruns the dusk of fate,

let us win bright honor while the sun is ours—

so when the river Xanthus hears our names,

fathers will say, ‘They fed our tables well,

and in the storm of bronze they did not break.’

Book: The Iliad (Book 12)

Author: Homer

The Pre-Greek Anatolian Connection

Western storytelling often treats Anatolia as a stage on which Greek and Roman actors perform. Xanthos proves the opposite. Here we see a native culture speaking an Anatolian branch of Indo-European (Luwian language group), worshipping in ways that predate and then reframe Greek cults, and building funerary monuments no mainland Greek city ever did.

Long before the arrival of the Greek colonists who began settling the western Anatolian coast in the early first millennium BCE—founding the Ionian and Aeolian cities that later dominated the shoreline—the interior highlands were already home to deeply rooted Anatolian peoples with their own languages, myths, and sacred landscapes.

In Hittite records, the Lycians of the classical age are known as the Lukkans; they call themselves the Termilae. The lands of Lycia—whose peaks are adorned with cedar and pine forests—harbor more than a hundred settlements amid majestic mountains and fertile plains washed by rushing waters.

As archaeologist Ümit Işın often stresses in his public talks and writing, the true story of Anatolia demands that we tell it on its own terms, correct popular “truths” that reduce the peninsula to a footnote, and foreground the extraordinary continuity from prehistory to the classical world. That’s exactly the lens we bring to Xanthos.

The Anatolian Roots: From Luwian to Lycian

Before we say “Greek influence,” remember what came first:

- Luwian-speaking worlds (Bronze Age): Western and southern Anatolia were home to Luwian languages long before the classical era.

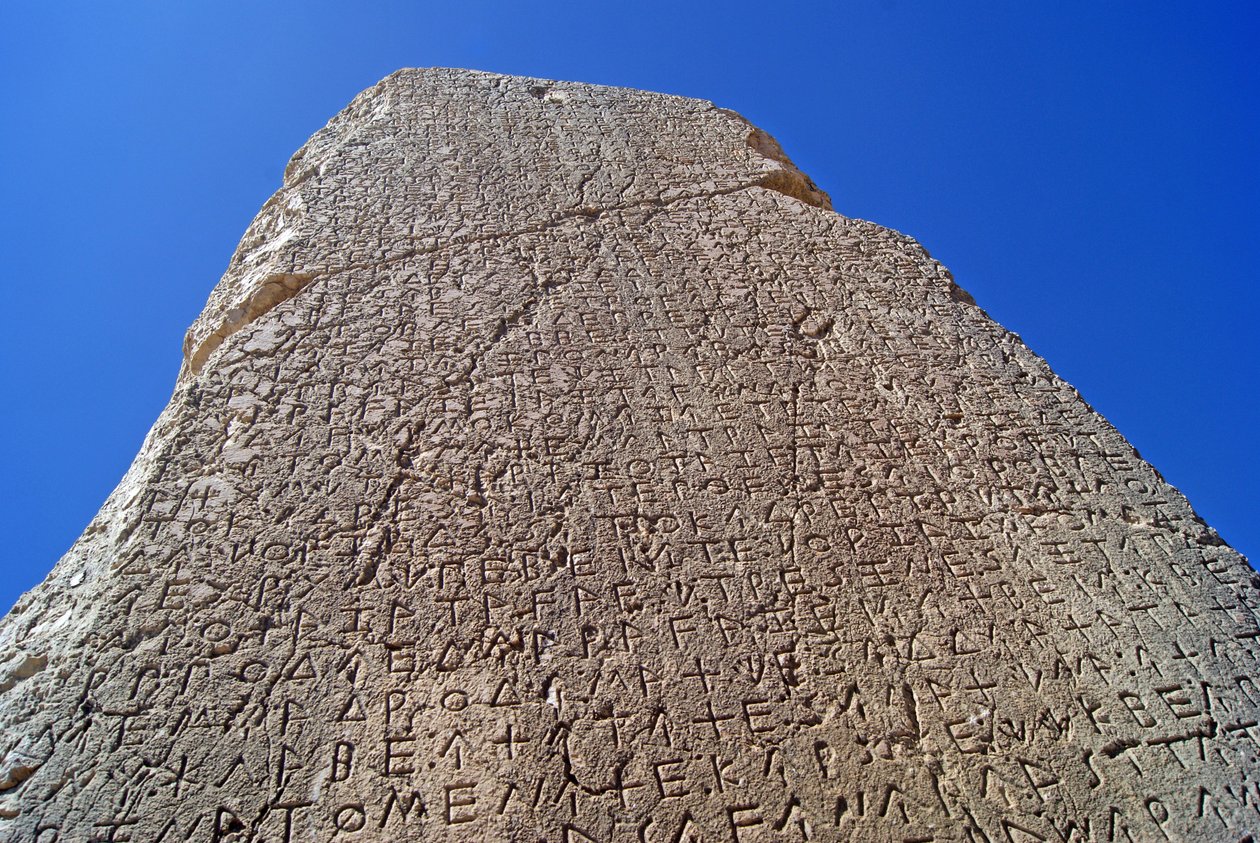

- Lycian language (Iron Age): Lycian—the language carved on Xanthos’s stones—belongs to the same Anatolian family as Hittite and Luwian, not to Greek. The Xanthian Obelisk (a tall inscribed pillar) preserves a long Lycian text (along with a related local dialect and a small Greek section), offering a rare native voice from 5th-century BCE Anatolia.

- Takeaway: Lycian is neither a Greek dialect nor a decorative veneer on “Hellenism.” It is an Anatolian language articulating an Anatolian civilization.

A City That Stayed Itself

Lycia formed a league of cities—an early model of confederation with representation weighted by city size. Xanthos, the largest and most influential, often led the league. Even under Persian oversight or within the Hellenistic and Roman spheres, Lycia’s political habits, funerary art, and language show continuity rather than capitulation

At Letoon, the cult of Leto (mother of Apollo and Artemis) was not a simple Greek import. Rather, Lycians layered Leto onto older Anatolian mother-goddess Cybele traditions, creating something locally meaningful. Lycian inscriptions also name local deities alongside Zeus and Apollo—an Anatolian pantheon conversant with its neighbors, not swallowed by them.

Art & Architecture: Distinctly Lycian

Walk the acropolis plateau and the terrace below and you’ll meet monuments that don’t read as “Greek” at all:

Pillar Tombs and Cliff Tombs: House-shaped sarcophagi raised on lofty pillars, and facades cut into living rock.

The celebrated Harpy Tomb (c. 480 BCE) is a towering stone chamber atop a pillar, once ringed with relief panels—an intensely Lycian way to honor the dead. Even when sculptural style looks “classical,” the programs, symbols, and contexts speak Lycian.

In 1838, Charles Fellows first visited Xanthos; by 1842–1844 he had the pillar-tomb reliefs crated to London and, seeing winged women through a Greek lens, branded the monument the “Harpy Tomb.” That mid-19th-century label stuck, and for decades Western experts followed his lead: Greek-looking carving (Ionian hands, archaic drapery) was read as Greek myth, full stop.

In 1838, Charles Fellows first visited Xanthos; by 1842–1844 he had the pillar-tomb reliefs crated to London and, seeing winged women through a Greek lens, branded the monument the “Harpy Tomb.” That mid-19th-century label stuck, and for decades Western experts followed his lead: Greek-looking carving (Ionian hands, archaic drapery) was read as Greek myth, full stop.

But Fellows was working before Lycian inscriptions and religion were remotely well understood (the language began to be seriously deciphered only from the 1840s–1850s, with major advances later), so the Greek reading filled a knowledge gap rather than reflecting local meaning.

What the reliefs actually stage is a Lycian dynast’s passage into honored ancestry—family gathered, attendants and soul-bearers around him—an Anatolian story told in an Aegean style.

The Greek-centric template hardened from the late 1800s through the mid-1900s, but since the 1990s–2020s Turkish archaeologists working at Lycia’s sites have pushed a course-correction: read the images in their local ritual context and history.

The result overturns the 1840s misnomer—Fellows got the stones to Britain, but modern scholarship gives them back their Lycian voice. The grand “Lycian-style” tomb form inspired monuments well beyond Lycia in the Classical and Hellenistic world.

Fire and Memory: The Two Conflagrations

Two episodes define the city’s mythos:

- 540 BCE: Besieged by Harpagus, the Xanthians set their acropolis ablaze and fought to the death rather than submit to Persia. Herodotus says the Xanthians, defeated in the plain and driven back into the city, gathered their families and property on the acropolis, set it ablaze, swore oaths, and rushed out to die fighting Harpagus’ army. He adds that only ~80 households survived because they were away from home.

- 42 BCE: Under pressure from Brutus in the Roman civil wars, they repeated the grim choice. Ancient authors describe a massacre and mass suicides, with only a small number of survivors.

These acts of collective resolve—however tragic—became part of Lycia’s identity: a people for whom freedom and honor outweighed survival.

Why do some sculptures look classical?

Sculptural styles moved across the Mediterranean. Lycians adopted techniques and motifs—but the functions, meanings, and monument types remained locally anchored.

“Beyond Greece”: Placing Xanthos in the Deeper Anatolian Timeline

To appreciate Xanthos fully, we should zoom out:

Neolithic Anatolia: Monumental cult sites like Göbekli Tepe (10th–9th BCE) show organized ritual communities millennia before the classical world.

Bronze Age mosaics: Hittite realms and Luwian polities shaped western and southern Anatolia.

Iron Age cultures: Lycia (with neighbors like Caria, Pamphylia, Phrygia, and Cilicia) carried forward local languages, pantheons, and art even as they interacted with Greeks and, later, Rome.

This deep-time view is what Anatolian archaeology contributes: continuity, transformation, and creative selection—not simple replacement.

Ümit Işın (paraphrased):

Anatolia is an open-air museum where civilizations didn’t merely arrive from elsewhere—they germinated, overlapped, and matured here. Our job is to restore that layered story, especially where popular narratives flatten it.

Get in Touch With Us

At The Other Tour, we approach Xanthos as Anatolia first—we read the Lycian language stones, trace the league’s politics, and feel the funerary landscape as the Xanthians built it.

If you want, we connect the dots across Lycia—Letoon, Patara, Tlos, Pinara—and, for the bigger picture, fold in Caria, Pamphylia, Phrygia, or Cilicia. This isn’t “classical sightseeing”; it’s Anatolian archaeology in the field—alive, layered, and human.

📅 Ready to explore?

Reach out here and let’s start planning your adventure. Whether you’re a history lover, a mythology geek, or simply curious, we’ll craft a visit that feels personal, thoughtful, and unforgettable.

Great piece. The way you explain the Lycian language and the Xanthian Obelisk inscription is spot-on. It’s one of those sites where a little background dramatically improves the visit.

Hey Metin, thank you. Xanthos really is special!