A handful of Greek-speaking, Jesus-loving Romans and their descendants still walk the streets of Istanbul today, a once-mighty community now reduced to a fragile remnant — yet from Istanbul’s Fener neighborhood, their ancient Patriarchate still dares to speak with the voice of an empire that refuses to die.

Table of Contents

Introduction to the Greek Orthodox Church

Hidden within the quiet backstreets of Fener, along the Golden Horn, stands one of the most historically significant religious institutions in the world: the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. Though modest in appearance, the Patriarchal Cathedral of St. George serves as the spiritual heart of Eastern Orthodoxy — a tradition followed by more than 300 million believers worldwide.

Its story stretches from the earliest days of Christianity to its modern role as a global voice for peace, dialogue, and environmental ethics. This is the deep, complex, and fascinating story of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.

But before all of that, it begins with one man:

Constantine the Great, the emperor who reshaped the world.

Constantine’s Footsteps: The Emperor Who Rebuilt the Roman World

Few rulers have shaped world history as profoundly as Constantine. His rise not only reunited a fractured empire but also forever changed the relationship between Christianity and the Roman state.

Reuniting a Broken Empire

After issuing the Edict of Milan in 313 and restoring unity to a battered empire, Constantine discovered that the Roman world’s new religion was anything but unified. Rival bishops, theological factions, and competing interpretations of Christ’s nature were tearing the Christian communities apart — none more rapidly than the controversy ignited by Arius, the Alexandrian presbyter whose catchy hymns and sailor-style street songs spread across the Mediterranean like wildfire.

Saint Helena's Son: Constantine

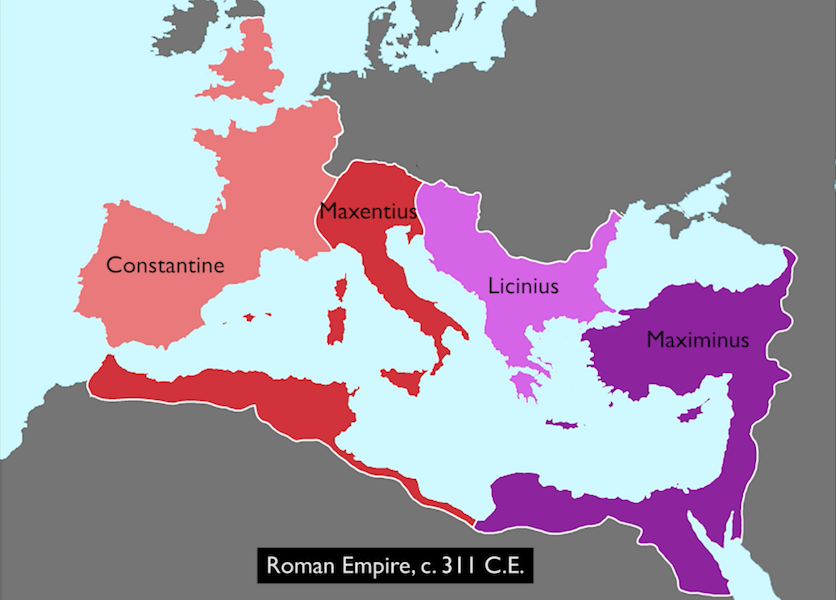

After the end of the Pax Romana, the Roman Empire entered a long period of crisis. By the early 4th century, it remained fractured by rival emperors and recurring civil wars.

Constantine’s ascent began with his dramatic victory at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (312), where he marched under a Christian symbol revealed, he believed, in a divine vision.

A year later, in 313, came a turning point for world religion:

the Edict of Milan, issued jointly by Constantine and his co-emperor Licinius.

For the first time in history:

Christianity became legal and protected,

Persecution ended,

Confiscated churches were restored,

Christians gained the freedom to worship openly.

The Edict did not make Christianity the state religion — that would come later (that would happen under Theodosius I exactly 67 years later) — but it allowed the Church to flourish, organize, debate, and build.

Over the next decade, Constantine consolidated power in the West.

Then, in 324, he confronted his final rival: Licinius, emperor of the East.

The Battle of Chrysopolis (324)

On the Asian shore of the Bosphorus, Constantine defeated Licinius and reunited the entire Roman Empire under a single ruler — the first in many decades.

With political unity achieved, he turned toward securing unity of faith.

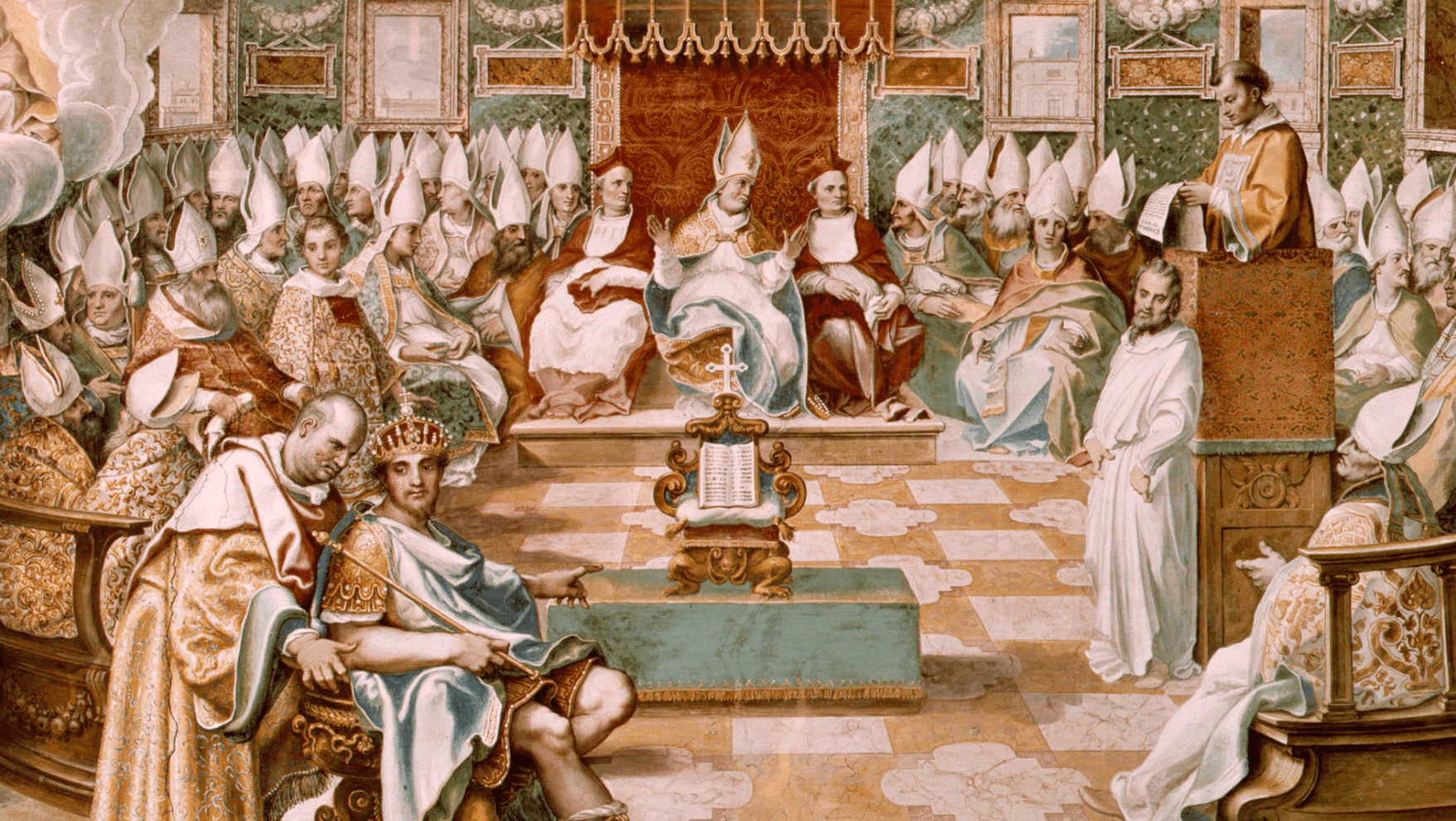

The Arian Controversy and The First Council of Nicaea (325)

Arius’ teachings — especially the provocative claim that

“there was a time when the Son was not”

— were being sung by dockworkers, merchants, soldiers, and even children in the marketplaces of Alexandria, Antioch, and Nicomedia. His popularity turned a local dispute into a crisis that threatened the very unity Constantine had just fought to restore.

The emperor, desperate to prevent a religious civil war inside his newly Christianizing empire, intervened. To restore harmony, Constantine convened the First Ecumenical Council in Nicaea (İznik). This gathering produced the Nicene Creed, the foundational declaration of Christian orthodoxy still recited around the world.

Nicaea marked the moment when Church and Empire became inseparable partners, shaping one another for centuries.

Founding the New Capital: Constantinople

Two years after Nicaea, Constantine made perhaps his most influential decision: he founded a new imperial capital on the ancient site of Byzantium.

In 330, he inaugurated Constantinople — “New Rome.”

A Christian Capital for a Christian Age

Constantine transformed the city with a grand imperial palace, forums and ceremonial squares, monumental gates and defensive walls, new administrative centers, and, crucially, the first major Christian churches.

Among the earliest were:

The Church of the Holy Apostles — destined to be Constantine’s burial place

The original Hagia Irene — one of the oldest surviving churches in the city

Early basilicas that laid the groundwork for the future Patriarchal seat

Constantinople was not simply a political project. It was the architectural and spiritual blueprint for a Christian empire — the stage on which the drama of Byzantine Orthodoxy would unfold.

The Rise of the Patriarchate

When Constantine founded his new capital, the bishop of Byzantium was still a minor figure. But a city as important as “New Rome” naturally demanded a prominent ecclesiastical leader.

- In 381, the Second Ecumenical Council declared that the bishop of Constantinople held second place after Rome, “because it is New Rome.”

- In 451, the Council of Chalcedon elevated Constantinople to a full Patriarchate, granting broad jurisdiction over the empire’s key regions.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate was born — an institution rooted in Constantine’s political and spiritual vision.

The Byzantine Era: Fortress of Orthodoxy

For over a millennium, the Patriarchate became the beating heart of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) world — shaping theology, guiding emperors, and preserving Christian tradition.

Doctrinal Battles That Defined Christianity

Patriarchs played decisive roles in the greatest theological debates of Late Antiquity:

The struggle against Arianism

The Christological controversies of the 5th century

The Iconoclastic Crisis (726–843), which nearly tore the empire apart

The ultimate triumph of icon veneration

Mission to the Slavs

From Constantinople, missionaries like Saints Cyril and Methodius traveled northward, bringing Christianity to the Slavic world — influencing Bulgaria, Serbia, Russia, Ukraine, and beyond, shaping the spiritual map of Eastern Europe.

The Islamic Reordering of the East

Through the 7th and 8th centuries, Islamic rule expanded rapidly across Syria, Palestine, Egypt, North Africa, and eventually much of eastern Anatolia. Subsequently, the Mediterranean world was transformed by the rise of Islam.

The Byzantine Empire felt the impact almost immediately, as Arab armies inspired by the new faith pressed hard against its borders, even bringing war to the very walls of Constantinople and coming perilously close to capturing the city.

It’s staggering to imagine how different world history might look if Constantinople had fallen that early — seven or eight centuries before the Renaissance.

This had far-reaching effects:

Rome and Constantinople drifted apart culturally and politically

Byzantium faced relentless military pressure

The empire increasingly saw itself as the last bastion of ancient Christianity

Iconoclasm and the Influence of Islamic Aniconism

Islam’s strict rejection of religious images influenced several Byzantine emperors during the Iconoclastic Crisis. Some saw early Islamic military victories as a sign of divine favor for aniconism.

Rome, which defended the veneration of icons, strongly opposed this movement — deepening theological tensions between East and West.

Arab Sieges and a Renewed Imperial Identity

The two great sieges of Constantinople (674–678, 717–718) reinforced a distinctive Byzantine identity — resilient, theological, and increasingly different from the Latin West.

The Great Schism (1054): A Divide Centuries in the Making

By the 11th century, the Greek East and Latin West had grown into two distinct civilizations, divided by language, liturgy, philosophy, and political pressures.

The mutual excommunications of 1054 simply formalized a separation centuries in the making, marking the beginning of the Great Schism between Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism.

The fracture deepened after the Byzantine defeat at Manzikert in 1071, which left the empire vulnerable and pushed it to seek help from the Pope — a move that helped spark the First Crusade (1095). But the deepest wound came in 1204, when Latin Christian armies of the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople.

For the Orthodox world, this was more than political betrayal; it was a spiritual trauma, a desecration of its holiest city. Even today, the memory of 1204 remains one of the most painful and enduring scars between East and West.

The Ottoman Era: Survival and Reinvention

When the Ottomans conquered Constantinople in 1453, they chose to preserve — rather than abolish — the Ecumenical Patriarchate, integrating it into the imperial system.

Under the Rum Millet established by Sultan Mehmed II, the Patriarch was recognized not only as the spiritual head of the Orthodox community but also as its civil leader, granting the office significant authority.

By around 1600, the Patriarchate settled permanently in the Church of St. George in Fener, which, despite fires, political pressures, and demographic shifts, became the enduring center of Ottoman Greek (Rum millet) life.

From this environment emerged the Phanariots, influential Greek families closely tied to the Patriarchate who served as diplomats, administrators, and intellectuals, helping shape Ottoman governance from within.

Modern Transformations

The 19th and 20th centuries brought dramatic transformations for the Patriarchate: national independence movements reshaped the Orthodox world, new autocephalous churches emerged, the population exchange between Greece and Türkiye emptied entire communities, and Istanbul’s Greek population sharply declined, shrinking the Patriarchate’s territorial influence. Yet even as its local presence diminished, its global spiritual role expanded, especially among growing diaspora communities.

This era also witnessed the emergence of the Turkish Orthodox Patriarchate (1922–present), a nationalist movement seeking to establish a distinct Turkish Orthodox identity within the early Republican context.

In recent years, the Russia–Constantinople break (2018–2022) further underlined the continuing geopolitical weight of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, as Moscow severed communion after Constantinople granted autocephaly to the Orthodox Church of Ukraine.

Contemporary Debate: Sevan Nişanyan’s Perspective

You can watch the video the auto-translate function on YouTube.

Writer and historian Sevan Nişanyan offers a provocative alternative interpretation of the Patriarchate’s role and legacy. His perspective is not mainstream, but it provides context for understanding modern Turkish attitudes toward the institution.

The writer argues that the Ecumenical Patriarchate today is best understood as a political heir of Byzantium, having inherited the empire’s sophisticated culture of diplomacy, strategy, and institutional complexity.

He also emphasizes that its continued residence in Istanbul — despite the city’s now-tiny Rum population — makes it a demographic anomaly, a universal patriarchate operating in a place where its traditional community has all but disappeared.

In his view, much of its historical authority stemmed from its role as the head of the Rum Millet, meaning its influence was always intertwined with imperial structures rather than rooted solely in spiritual leadership.

If you want to stay clear of the Ottoman Empire‘s influence, you distant yourself from the Istanbul Patriarchate. (Sevan Nısanyan)

At the same time, he describes a weakened center struggling with limited resources, staffing challenges, and an often-delicate relationship with the Turkish state. This stands in contrast with the worldwide Orthodox network, which he believes remains vast and culturally influential, yet insufficiently utilized as a potential asset for Türkiye.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate Today

The current Ecumenical Patriarch, Bartholomew I (since 1991), is known worldwide as:

A pioneer of environmental advocacy (“The Green Patriarch”)

A leading voice in interreligious dialogue

A global representative of Orthodox Christianity

A bridge between ancient tradition and contemporary challenges

Despite a small local flock, the Patriarchate’s international influence remains profound, especially among diaspora communities in Europe, Africa (Ethiopia in particular), North America, and Australia.

Inside the Patriarchal Cathedral of St. George

Despite its modest exterior, St. George’s Cathedral houses treasures of extraordinary spiritual and historical significance:

Relics of St. John Chrysostom and St. Gregory the Theologian

A magnificently carved wooden iconostasis

The ancient patriarchal throne

Miraculous icons venerated for centuries

And one of its most moving relics: a fragment of the column believed to be the one where Jesus was tied before the Flagellation

Quiet, intimate, and filled with living history, St. George’s remains one of the holiest sites in the Orthodox Christian world.

Why the Ecumenical Patriarchate Matters

Today, the Ecumenical Patriarchate – and the Greek Orthodox Church more broadly – stands as:

A living link to the apostolic age, preserving forms of worship, theology, and church life that reach back to the earliest Christian communities.

The historic “First Throne” of Orthodoxy, carrying the primacy of honor among the ancient patriarchates of the Christian East.

A guardian of the old Hellenistic–Roman Christian tradition, keeping alive the language, liturgy, and intellectual world of the Eastern Roman Empire – a kind of holy “relic” of late antiquity that still breathes.

A church that prays and thinks in Greek, where the spirit of Jesus is proclaimed, sung, and contemplated in the very language of the New Testament and the early councils.

A symbol of resilience, peace, and dialogue, surviving empire, conquest, nationalism, and modern secularism while engaging other churches, religions, and states with surprising patience.

A reminder of Istanbul/Constantinople’s role as a crossroads of civilizations, where Greek, Roman, Jewish, Armenian, Slavic, Arab, and Turkish histories intersect – and where that layered story is still told every time the Divine Liturgy is celebrated at the Phanar.

Get in touch with us & Visit the Patriarchate

Visiting the Ecumenical Patriarchate is like stepping into a living chapter of world history.

Whether you are drawn to theology, architecture, liturgy, or simply the hidden corners of Istanbul, Fener offers a journey into a world that shaped continents.

Let’s explore Fener, Balat, and the Golden Horn together — discovering stories most travelers never hear.

Just came across your article in my google feed and i gotta say that i’m really thankful as my family family has roots in istanbul and i plan to visit next summer. so this fits like a glove! i’ll be sure to check out your tours as well. looking forward to visiting the patriarchate when i’m there.

Thank you so much for your kind words! I’m really glad the article reached you and even happier that it resonated with your family’s connection to Istanbul. Whenever you’re in the city next summer, feel free to reach out — I’d love to show you around and help you explore the Patriarchate and the neighborhood’s hidden stories. Safe travels and hope to meet you soon!